BLOG

Finds and Interests

Image Source: Wikimedia

These days, everyone has a camera in their pocket. Taking photos to commemorate special—and not-so-special—occasions seems like second nature. Snapping photos at a wedding or graduation is commonplace. Snapping pictures of your dinner is commonplace but not so unique.

In the 18th century, when a memento of a special occasion (or significant person) was wanted, the landed gentry sat for formal portraits. But portraits were time-consuming and expensive. Working stiffs couldn’t afford such a luxury.

However, silhouette portraits became the rage in the early 18th century. Gentry and commoners alike were keen on these new images. They were quickly executed, inexpensive, and readily available.

Silhouette portraits were everywhere. They could be found hanging on walls next to oil paintings, tucked into tabletop frames as décor, and collected in memory albums. Silhouettes held even more meaning when worn as jewelry, such as lockets or brooches. This allowed the wearer to keep their loved ones close at all times and served as a constant reminder of those who couldn’t be present.

18th-Century Facial Recognition

Silhouette portraits have very little detail. Almost none, in fact. So, how can the images be linked to particular individuals? If you were to compare a full-face image to a silhouette of the same person, you would quickly discover that the profile view (silhouette) provides more points of identification. A profile view relies heavily on the proportions and relationship of the bony structures of the face (the forehead, nose, and chin), which results in a clear and straightforward image. Studies with silhouettes show humans can extract accurate information about gender and age from a silhouette alone.

Image Source: Wikimedia

Productivity Tools for Low-Tech Portraiture

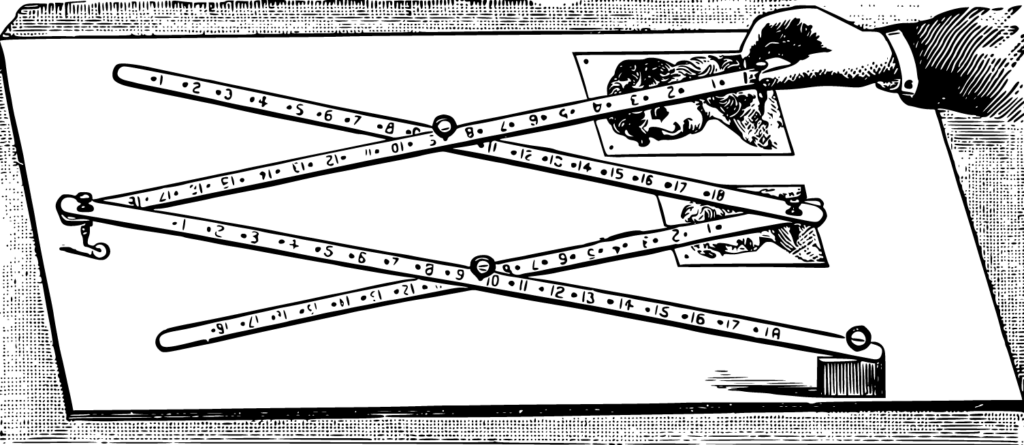

While some artists created their clients’ portraits using only ambient light, scissors, and paint, others outlined the contours of a subject’s face using a pantograph connected to a pencil. An artist could outline a profile contour on paper within a few minutes. Then, if a client wanted the silhouette miniaturized, the artist would use a second, reducing pantograph to scale down the image.

A reducing pantograph is a device used to duplicate and shrink an image or drawing. It works by moving numerous connected bars in parallel. The original image is placed on one end of the pantograph, and as it moves across the surface, a pointer attached to another bar copies its lines onto a new sheet of paper at the other end. A series of levers then change the picture proportions from one side to the other, generating a smaller duplicate. Thus, the result is a properly scaled-down version of the original image or picture, suitable for tabletop framing or jewelry design.

The William Bache Silhouette Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery

Silhouette artists established studios in most major cities by the end of the 18th century, and many wandering artists offered their skills in smaller towns. Advertisements in local newspapers promoting the artist’s quickness, accuracy, and unique technique helped artists stand out from the crowd. Eighteenth-century silhouette artist William Bache went door-to-door along America’s eastern seaboard selling a set of four portraits for twenty-five cents (about five dollars in today’s money).

Bache’s work has recently been digitized and displayed in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery’s William Bache silhouette collection. It depicts the essence of 18th-century life, love, and society. These intimate images are intriguing and exemplify the ongoing appeal of this art form.

Silhouette portraits provide a unique glimpse into our past that no photograph can match. They are not just profile images; they are windows into another time. So, next time you view one, take a moment to appreciate its beauty and significance. And if you happen to be in Washington, DC, visit The William Bache silhouette collection at the National Portrait Gallery for an immersive journey into a once-prominent art form.

Image Source: HistoryInPhotographs.com

Is There a Silhouette Portrait in Your Past?

With the advent of photography, the term “silhouette” shifted in meaning. In the 20th century, it can also mean a dark image against a lighter background. You likely have such photos in your family photo albums. I do, along with several excellent examples in my History in Photographs website.

A generation or two ago, schoolchildren made silhouettes as a class project. A child sat on a chair while another aimed a bright light across the profile of the sitting student. A profile shadow was cast onto drawing paper, where the shadow was traced. Then, the tracing was cut out, placed on black construction paper, recut, and mounted. Thousands of 20th-century profile portraits are likely in memory boxes and albums across America. Parents loved these things and kept them. Students had fun making them but then moved on to other projects.

Will Seippel is the CEO and founder of WorthPoint®, the world’s largest provider of information about art, antiques, and collectibles. An Inc. 500 Company, WorthPoint is used by individuals and organizations seeking credible valuations on everything from cameras to coins. WorthPoint counts the Salvation Army, Habitat for Humanity, and the IRS among its clients.